Doc Talk: Dr. Amit Dotan

Wednesday, June 22, 2016

Each year, the Montreal Children's Hospital welcomes dozens of fellows from abroad thanks to a mix of donor support and public grants. These physicians strive for excellence and their stories are truly inspirational. In this edition of Doc Talk, meet Dr. Amit Dotan, whose work spans three continents.

Dr. Dotan, you could practice medicine in Israel, your country of origin, yet you decided to come to Canada. Why is that?

My wife, an internal medicine specialist, and I wanted our family to experience a different culture. Dr. Mark Clarfield, formerly from McGill and now the dean of an international medical school of the Columbia University in Jerusalem, attached to the hospital where I worked, spoke to us about the excellent training we could get at the Children’s. We felt it was a natural fit and we were grateful to count on scholarships to help us move here.

Was it difficult to find a home and everything associated with such a big move?

The hard part is not the move per se. We got acquainted with Israelis in Montreal and they reserved an apartment for us after we saw pictures. It is more about finding the balance between our demanding work and our three children. In Israel, the grand parents were there to help. But here, we had to adapt our schedule. My wife and I alternated our time in the research lab because it offers more flexibility, but there have been months where we both had intense periods as physicians. Fortunately, we can count on our friends to help out.

Why did you choose to specialize in hematology-oncology?

I knew it was what I wanted to do on my very first day at medical school. Cancer is often a scary word. Although it is emotionally hard because you witness families who feel like their world is breaking down, it is more optimistic than what people think: most children survive. I like the fact I can bring the psychological support to the families, that my work goes beyond the medical aspect.

Is it in the same spirit that you opened a clinic in a small village in Ethiopia?

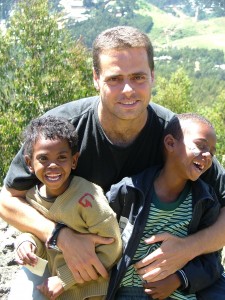

Yes. I was given an opportunity during my school years to work as a medical student in Addis Ababa. My wife came with me. I ended up preferring more volunteering in an orphanage for HIV positive kids. Back then, there were no specific treatments for these kids but children were still treated medically by Sister Maria who managed the place. Each week, at least one child died. When specific treatment did arrive, we implemented a system to ensure these kids took all their medication. We were treating them very intensively all the while trying to give them the emotional support every child needs, especially in an orphanage: play, do homework… When we heard some nuns were having difficulty establishing a clinic in a village called Zizencho, it really appealed to us. Ethiopians are considered poor to the western world but they have happiness and balance in their lives. I felt privileged to live among them during that time.

Each year, the Montreal Children's Hospital welcomes dozens of fellows from abroad thanks to a mix of donor support and public grants. These physicians strive for excellence and their stories are truly inspirational. In this edition of Doc Talk, meet Dr. Amit Dotan, whose work spans three continents.

Dr. Dotan, you could practice medicine in Israel, your country of origin, yet you decided to come to Canada. Why is that?

My wife, an internal medicine specialist, and I wanted our family to experience a different culture. Dr. Mark Clarfield, formerly from McGill and now the dean of an international medical school of the Columbia University in Jerusalem, attached to the hospital where I worked, spoke to us about the excellent training we could get at the Children’s. We felt it was a natural fit and we were grateful to count on scholarships to help us move here.

Was it difficult to find a home and everything associated with such a big move?

The hard part is not the move per se. We got acquainted with Israelis in Montreal and they reserved an apartment for us after we saw pictures. It is more about finding the balance between our demanding work and our three children. In Israel, the grand parents were there to help. But here, we had to adapt our schedule. My wife and I alternated our time in the research lab because it offers more flexibility, but there have been months where we both had intense periods as physicians. Fortunately, we can count on our friends to help out.

Why did you choose to specialize in hematology-oncology?

I knew it was what I wanted to do on my very first day at medical school. Cancer is often a scary word. Although it is emotionally hard because you witness families who feel like their world is breaking down, it is more optimistic than what people think: most children survive. I like the fact I can bring the psychological support to the families, that my work goes beyond the medical aspect.

Is it in the same spirit that you opened a clinic in a small village in Ethiopia?

Yes. I was given an opportunity during my school years to work as a medical student in Addis Ababa. My wife came with me. I ended up preferring more volunteering in an orphanage for HIV positive kids. Back then, there were no specific treatments for these kids but children were still treated medically by Sister Maria who managed the place. Each week, at least one child died. When specific treatment did arrive, we implemented a system to ensure these kids took all their medication. We were treating them very intensively all the while trying to give them the emotional support every child needs, especially in an orphanage: play, do homework… When we heard some nuns were having difficulty establishing a clinic in a village called Zizencho, it really appealed to us. Ethiopians are considered poor to the western world but they have happiness and balance in their lives. I felt privileged to live among them during that time.